Here are some facts about a natural disaster, tuberculosis.

According to WHO, in 2016:

10.4 million people fell ill with TB, and 1.7 million died from the disease.

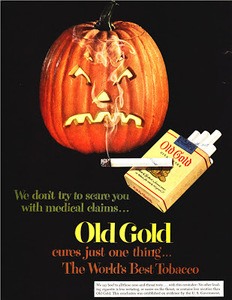

And now here are some facts about an unnatural disaster, smoking.

Tobacco kills more than 7 million people each year. More than 6 million of those deaths are the result of direct tobacco use while around 890,000 are the result of non-smokers being exposed to second-hand smoke. (WHO, 2018.)

Prevention and treatment of tuberculosis justify and require every effort being made to eliminate this scourge.

But smoking – a much more serious problem in terms of the numbers of deaths it causes – doesn’t seem to be taken as seriously by governments or government agencies.

If the bath is overflowing, it won’t solve the problem even if you sedulously mop up the water; you need to turn off the tap (faucet). It’s unacceptable, a scandal, an indictment of government policies, or, to put it simply in the parlance of today, it’s insane that cigarettes are freely available for purchase all over the world except in the enlightened country of Bhutan.

My critics will argue that real strides are being made by what is called Tobacco Control, to reduce the prevalence of smoking by instituting measures agreed internationally under the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC). These include the following;

- Higher tobacco taxation

- Requirement for warning labels and horrible pictures of diseases caused by smoking to be shown on cigarette packs

- Use of plain packs for cigarettes

- Restrictions on where smoking is allowed in public places

- Prohibition of advertising for tobacco products

- Provision of free stop-smoking clinics

They will point out, with some justification, that especially in higher income countries where these measures have been inaugurated (albeit with varying degrees of completeness), the prevalence of smoking has declined.

Obviously, the fewer people who smoke the better. But we are still left with two serious problems.

Smoking for years or decades

Smokers, or the vast majority of them, don’t quit merely as a result of the blandishments of the anti-smoking lobby after smoking a few cigarettes or after smoking for some weeks or months. Typically, once they start, many smokers continue smoking for years or decades. Then they may realise, having contemplated for the thousandth time the horrible pictures on the cigarette packs, that they had better quit. So they do it, often with a struggle involving a number of so-called quit attempts and in many cases with using nicotine maintenance therapy, prescription drugs, attending stop smoking clinics, undergoing hypnosis, etc. Then they quit, but are often at risk of relapse to smoking.

Now, let’s assume that our typical smoker quits permanently after having smoked, say, twenty cigarettes a day for twenty years. All is well, and after a few years his or her risk of dying from a smoking-related disease is the same as someone who’s never smoked? Except it isn’t.

The cumulative damage to the smoker’s DNA after decades of daily exposure to the poisons in cigarette smoke may result in the development of lung cancer even years after quitting. (In contrast, the risk of strokes and heart attacks will probably decrease after some years to that of someone who’s never smoked.)

And here’s another problem. Before the tobacco controllers give themselves a pat on the back, they should consider the plight of those unfortunates who are still smoking in spite of all the effort that has gone into effecting the bulleted points above.

In 2016, 15.8 per cent of adults in the UK smoked. By 2017 this had fallen to 15.1 per cent (Office for National Statistics), a decline of 0.7 per cent per year. If this rate of reduction continues it would take 22 years for the smoking prevalence to reach zero. But this only looks at current smokers. We also need to consider the more than 200,000 children aged 11 to 15 who start smoking every year in the UK. (Various sources.)

Concern for failed hope, unnatural disaster, and insanity

In New Zealand there is concern that the hope of making that country smoke-free by 2025 will not be realised. Therefore, there have been calls to make the sale of cigarettes illegal by this date. This is surely the only way for New Zealand or any other country to become smoke-free, though critics of such a proposal have expressed concern about making a currently legal activity, smoking, illegal.

This is the whole problem: smoking is legal in most parts of the world. And that is why more than 7 million people in the world die from a smoking-related disease every year.

If this unnatural and unnecessary disaster doesn’t epitomise insanity, I don’t know what does.

Text © Gabriel Symonds

Leave A Comment