Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) with its punny acronym of a name seems reluctant to embrace the only action that would solve the smoking problem once and for all: calling for banning tobacco. I recently asked their Chief Executive, Ms Deborah Arnott, by email, twice, whether this is ASH’s policy, and if not, why not. The answer was no reply. Or the reply was no answer.

Instead, the action that this organisation seems to favour is of the following kind.

Deborah Arnott:

There are currently 2.9 million e-cigarette users in Great Britain, over half of whom have quit smoking. E-cigarettes are playing an important role in supporting smokers to switch from tobacco smoking…As the market continues to develop we hope to see products go through the more stringent licensing process and become licensed as medicines and available on prescription. (Source: ASH Daily News 4 July 2017)

The sentence ‘E-cigarettes are playing an important role in supporting smokers to switch from tobacco smoking’ is muddled.

Presumably Ms Arnott means e-cigarettes can help smokers switch from tobacco smoking to e-cigarettes, but this isn’t very satisfactory either. Let me try again: e-cigarettes have a role (we can forego the ‘playing an important role’ cliché) in helping smokers switch from smoking to other, allegedly safer, ways of satisfying their nicotine addiction.

The end of the paragraph is more promising but likewise doesn’t seem to have been properly thought through.

If alternative nicotine products (alternative to cigarettes, that is) become licensed as medicines and available on prescription, that implies they won’t be available for the general public to buy in every corner-shop and supermarket. And they will, presumably, be prescribed only for a limited time—the time that it will be deemed sufficient for a smoker, having switched to an alternative product, then to stop using that product in the same way that patients stop using a prescribed drug when the have recovered from the illness for which it was prescribed.

This sentence also shows confusion about the idea of products being licensed as medicines. Although it certainly has effects on the human body, nicotine has no current orthodox medical use unless one stretches the concept to include treatment of nicotine addiction. But this would be contradictory because it would mean using nicotine for a limited time to treat nicotine addiction!

Nonetheless, if it is accepted, as it seems to be by the likes of Ms Arnott, that medicinal nicotine can legitimately be used as an indefinite treatment for cigarette-induced nicotine addiction, then we shall have the situation where doctors—presumably the burden will fall on GPs who already have more than enough to do—will have to take on the additional task of treating nicotine addicts, that is, smokers, who will likely flock to them for prescriptions for cigarette replacement therapy.

This defeatist and muddled thinking over using e-cigarettes to stop smoking is all too widespread. Even as far away as India, where a number of states have banned e-cigarettes, The Indian Express (3 September 2017), quotes unnamed experts as saying: ‘E-cigarette ban wipes out less harmful alternative for smokers.’

It does not appear to have occurred to these experts that not only is there a less harmful alternative for smokers, there is a completely harmless alternative for smokers: not smoking at all. And no one needs any nicotine product as an alternative for smoking!

In any case, are e-cigarettes really so much less harmful than ordinary cigarettes?

Other Indian experts think not. I quote again from The Indian Express:

…the Union Health Ministry has recently ruled out acceptability of e-cigarettes in the light of research findings by experts who concluded that they have cancer-causing properties, are highly addictive, and do not offer a safer alternative to tobacco-based smoking products.

So there. Ms Arnott please note.

Text © Gabriel Symonds

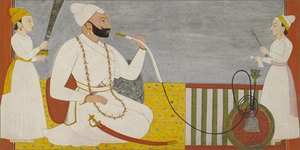

Photo credit: Wikimedia

Leave A Comment